Five years ago this month, I lived through the most traumatic experience of my life. I incurred major losses, both material and intangible, and before I could heal, I needed space to feel that pain and integrate my shock, which meant a couple of years of deep depression.

That summer, I moved to Boston, the home of Life is Good, Inc., a company dedicated to selling clothing and accessories with optimistic mottos. Almost daily, I saw someone wearing or carrying a branded item bearing what felt like an admonition. From friends to strangers to store windows, the message blared: “Life Is Good!” As if I was alone in going through a rough time, and if I couldn’t see the goodness in life, that was just one more failure on my part.

Therapy, supportive friends, reflection and writing, and a couple of years of anti-depressants helped me move beyond despondency and build a new life for myself. I’m happier today than I’ve been in years. But I don’t regret my depression: I believe it was an acceptable part of my process of healing, and an understandable expression of my grief, anger and loss.

I don’t impute bad intentions to the makers or wearers of Life is Good. In fact, several friends who wore this brand were among the most supportive and helpful in my healing. They listened to my experiences non-judgmentally and helped me feel connected, valued, and eventually able to see a path forward. In truth, life is good. It is also, in the immortal words of Thomas Hobbes, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Life is unfair and full of danger, and while controlling our outlook can be a source of strength, choosing to see life as good is not always the best coping strategy.

Recently, activist Anil Vora expressed a similar ambivalence about the It Gets Better Project. Sharing words of encouragement to help LGBT youth feel less alone and spark a conversation about bullying and discrimination are laudable goals. But as Vora points out, “for many LGBT people it only gets different, not better, and for many others it actually gets worse…” People who don’t identify with the gender they were assigned and people whose love is not exclusively heterosexual continue to face institutional, structural, legal and cultural barriers to equality. Minimizing that reality runs a risk of alienating or erasing some people’s experiences. A more powerful approach is to celebrate people’s ability to make choices that support their lives and transform society for the better. In fact, winning equal rights takes activism and movement-building which are only possible after facing the reality of the problem, coupled with faith that things can change. To me, that is the wisdom of Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.”

This is not a condemnation of good intentions but a call to empathy. A caution that such declarative language can be discouraging for those whose experiences at any given moment might not be good, and whose feelings are still valid. That summer, I needed to feel my loss, to process my experience and find a way forward that respected the lessons I had learned. I can’t even count the men who told me to smile during that time; seeing the ubiquitous message that “Life is Good” felt like an accusation that I was wallowing, and it made me feel more alienated and alone than I actually was.

You can make your life and the world better and there is good in life aren’t as pithy, but universalizing statements can do more harm than good. To encourage others and help them feel hope, in my experience really listening and connecting is always more effective than telling someone how they should or will feel.

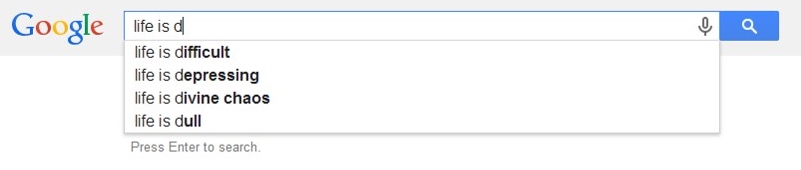

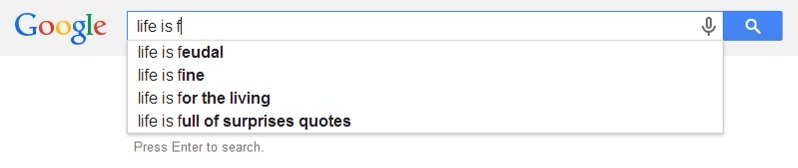

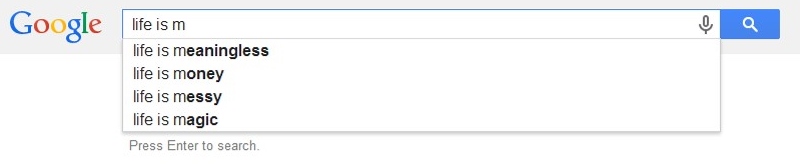

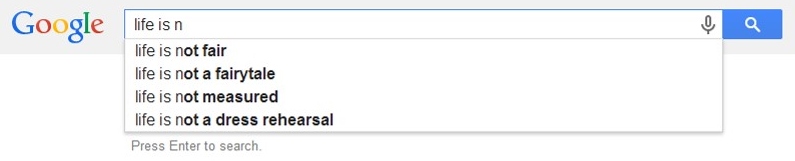

I’ll close with a few Google searches that make me feel less alone in my ambivalence: