As people in the U.S. commemorate the colonization of this land with the Thanksgiving holiday and National Day of Mourning, two current court cases remind us that the genocide underlying that occupation continues, centuries beyond the initial conquest.

On its face, Haaland v. Brackeen is a custody challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act’s protections against separating Native children from their kin. But by redefining Native status as a racial identity rather than nationalities, the case threatens to overturn the entire basis for Indigenous sovereignty and rights. This is clearly the goal of the law firm Gibson Dunn, which represents corporate clients including Chevron, Shell, and Energy Transfer, the company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). Gibson Dunn offered pro bono representation to the Brackeen plaintiffs just months after Indigenous water protectors cost their client billions in lost revenue.

Meanwhile, a Minnesota court is assessing the constitutionality of Enbridge Inc.’s funding, training and influencing the strategy of state forces charged with suppressing the indigenous-led resistance to its Line 3 pipeline.

While the corporate prerogative to exploit land and natural resources is an obvious driver in the second case, Indigenous commentators are clear that the ongoing genocide perpetuated by the separation of Native families has also always served that same agenda.

I don’t write to dictate strategy or speak over the voices linked above: anti-colonial struggles must be led by those indigenous to the land. My wish is to highlight these connections for the comrades with whom I’ve spent decades organizing against corporate power and abuse. We would do well to heed the lessons from these cases.

Corporations are just a tool that the same ruling class has used to exert its will and evade accountability since the first European settlers staked their claim to this continent. From the Mass Bay Colony to the Virginia Company, this land was colonized by corporations, which were the original governing entities from the outset.

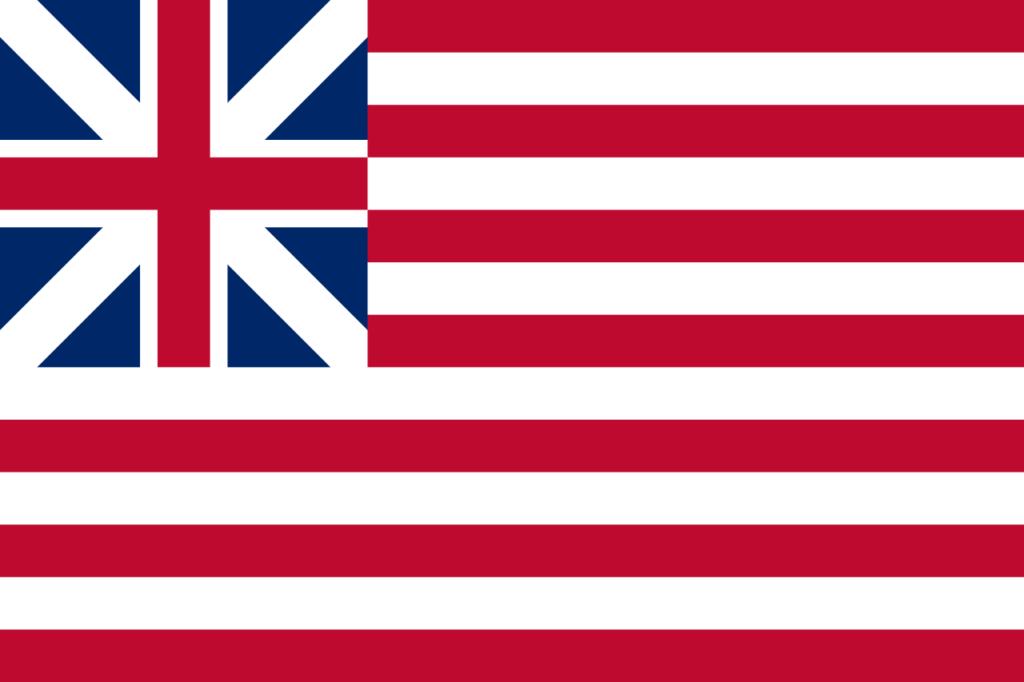

Even after the so-called Revolution, the new nation’s first flag:

was obviously based on the flag of the British East India Company:

This visible continuity of our governing institutions from the initial colonization to the modern nation should clarify the terrain of contemporary struggle. The obstacle to justice today is the same as it ever was: corporations and government agencies alike represent the interests of a ruling class that controls both.

We should be wary of any strategy that assumes corporations and the state are oppositional forces: neither will transform the extractive social order they have constructed and enforced without sustained, organized pressure. There is no single map for a just transition, but there is also no tactical shortcut for building the power of ordinary people. As we reflect on the history this weekend, let’s make sure to connect this context to all of our struggles confronting the current face of corporate power. Only by standing together, in concrete solidarity against the shared colonial project of state and corporate violence, can we create a freer, more humane future.